Race, Corruption, Morality and the Making of Anglo-India

Justice Pulbandi and the hanged Maharaja

– MJ Akbar

DUSTOORY LEAPT EFFORTLESSLY from the Persian of sultans into the English of British rule. It meant the usual, or the customary. Hobson-Jobson, always a stickler for detail, calls it:

That commission or percentage on the money passing any cash transaction which, with or without acknowledgment or permission, sticks to the fingers of the agent of payment. Such ‘customary’ appropriations are, we believe, very nearly as common in England as in India; a fact of which newspaper correspondence from time to time makes us aware… [Hobson-Jobson, page 333]

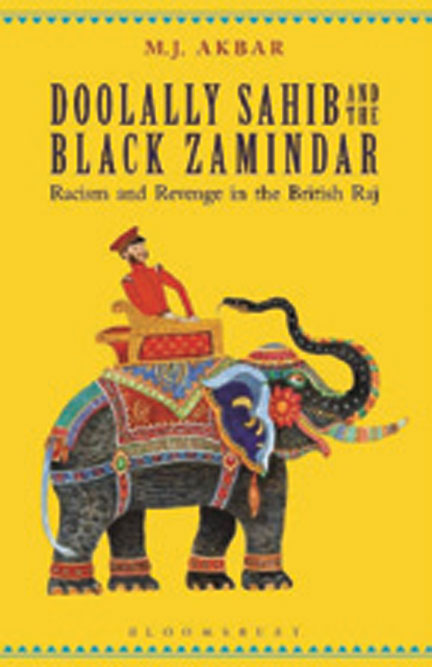

Bloomsbury

The percentage was flexible. The bribe could be 10 per cent of the contract or more. The dictionary quotes Hicky’s Bengal Gazette of 29 April 1780: “It can never be in the power of a superintendent of Police to reform the numberless abuses which servants of every Denomination have introduced, and now support on the Broad Basis of Dustoor.” Indo-British relations prospered best when Company officials, and the new Indian elite they spawned, cooperated in corruption. Anthony Weltden, the governor of Calcutta in 1710, assigned negotiations for graft to his wife and daughter not because he was squeamish, but because they ensured a better bargain.

Gobindaram Mitra, the deputy collector of Calcutta between 1720 and 1726, was anointed the first “black zamindar” by his British masters. Mitra’s official duty was to extract revenue, which he did through unorthodox methods. His cudgel-wielding goons, called paiks, naibs and naiks, were let loose upon the citizenry. This triptych became the template of the future Calcutta police, the equivalent of constables, head constables and investigating officers.

Gobindoramer chhodi, or Gobindaram’s stick, entered popular parlance as a metaphor for abuse of power. Expanding this clout, Mitra became Calcutta’s first godfather of white-collar crime: inflating tenders, fudging accounts, manipulating auctions for public works or land sales which were conducted from his home to emphasize his control over the outcome. He monopolized the best deals, often under fictitious names, inflated contract estimates for repairs or construction and split the excess with the contractor. In a typically brazen instance, he won the auction for 18 bazaars and rented out the property immediately, collecting a 100 per cent advance from the tenants. In other words, he became a commercial landowner without spending a rupee.

Indo-British relations prospered best when Company officials, and the new Indian elite they spawned, cooperated in corruption. Gobindaram Mitra, the deputy collector of Calcutta between 1720 and 1726, was anointed the first ‘black zamindar’ by his British masters. Mitra’s official duty was to extract revenue, which he did through unorthodox methods

Mitra’s luck ran out in 1752, when John Zephaniah, the new governor, demanded accounts. However, his large reserves of chutzpah remained intact. Mitra replied that all records till 1738 were lost in the great storm of that year, and the rest had been eaten by white ants. The zealous Zephaniah prosecuted, but Mitra escaped with the support of complicit officials. In the proper style of a mafia don, his remit ran to the judiciary.

Sumanta Banerjee writes:

Ironically enough, the trendsetters in the art of crime in the early days of Calcutta were not the poor rogues from the city’s underworld, but the British lawmakers and the Bengali privileged classes, who struck deals with each other, and helped themselves to money and property by dispossessing the people and milking resources. [Crime and Urbanization: Calcutta and the Nineteenth Century, Tulika Books, 2006, page 1]

Calcutta was powerful, ambitious, wanton, and delinquent. Clive, no mean hand at self-enrichment, described the city in 1765 as “one of the most wicked Places in the Universe. Corruption, Licentiousness and a want of Principle seem to have possessed the Minds of all the Civil Servants, by frequent bad examples they have grown callous, Rapacious and Luxurious beyond Conception…” [British Social Life in India, Kincaid, page 110]. A less famous but sharp-eyed observer, Mrs Sherwood, describes how precisely luxurious it was:

…the splendid sloth and the languid debauchery of European society in those days—English gentlemen, overwhelmed with the consequences of extravagance, hampered by Hindoo women and by crowds of olive-coloured children…Great men rode about in State coaches, with a dozen servants running before and behind them to bawl out their titles; and little men lounged in palanquins or drove a chariot for which they never intended to pay, drawn by horses cajoled out of the stables of wealthy Baboos. [British Social Life in India, Kincaid, page 110]

The Army was as infected as the civilian merchants. General Richard Smith was considered dissolute and tyrannical in addition to being corrupt; Calcuttans ridiculed his manners but were terrified of his power. Clive went back to England, unable to do much.

Warren Hastings rejoined the East India Company after the fortune he had amassed from his first stint was lost by mismanagement, his despair compounded by the death of his wife and son. On the ship to Madras, he fell in love with Anna Maria Chapuset, the wife of an itinerant baron without much money. Hastings gave Maria, renamed Marian, a dower of Rs 100,000 on their marriage. She wore a gown trimmed with fine point and a cap full of diamonds and pearls at their first public appearance after the wedding. The man who gave her away was a schoolfriend of the groom, Sir Elijah Impey, recently appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William.

Calcutta was in the grip of fortune hunters, gamblers, and conspirators. In 1774, three members were added to Hastings’s governing council: Philip Francis, just 33 years old, along with two older Army officers, General John Clavering, first member and commander-in- chief, and Colonel George Monson, each on a handsome annual salary of £10,000. The three conspired with such vitriolic intensity against Hastings, “so sensitive to rebuke and so proud of his character”, that he “could not breathe in this air of unrelenting malice”, according to a biographer. [Warren Hastings, Keith Feiling, Macmillan, 1954, page 188]

Malice, however, had value. Francis was assured, after a year in Calcutta, that Hastings was ready to buy off the three allies for £100,000 apiece. This was equivalent to a British prime minister silencing his Cabinet colleagues with money. It also indicated how much money Hastings had. Hastings was justifiably anxious. An Indian aristocrat with incriminating documents had joined the power struggle.

Nandakumar, awarded the title of “Maharaja” by Emperor Shah Alam in 1764, was among the wealthiest and most influential nobles of Bengal. “In appearance,” writes H.E. Busteed, “he has been described as tall and majestic in person, robust, yet graceful. When the misfortune which has immortalized his name befell him he was nearly seventy years of age.” [Echoes from Old Calcutta:

Reminiscences of the Days of Warren Hastings, Francis and Impey, Busteed, 1908; republished by Rupa, page 105]

On 11 March 1775, Maharaja Nandakumar wrote to the governing council accusing Hastings of having taken £45,000 as a bribe from him and Mir Jafar’s widow Munni Begum, through his agent Kanta Babu to make certain appointments. He produced vouchers as evidence. The council ordered a humiliated Hastings to pay the equivalent amount into the treasury.

Nandakumar was neither naïve nor politically innocent; he was party to an attempted coup against Hastings. Nor was his ally Francis a saint, having filled his own pockets whenever he got the opportunity, even as he consoled his conscience with the specious argument that he was merely bleeding bloodsuckers. What they did not expect was Hastings’s counteroffensive through Impey. On 19 April 1775, the government prosecuted Nandakumar for conspiracy. On 6 May he was arrested for forging documents.

Attitudes began to improve only after liberals like Henry Beveridge entered the civil service in 1857. The Beveridges were benevolent towards their domestic staff and treated them like family. Annette could become motherly

The imperious Brahmin Maharaja chose a lofty response. He claimed he could not stay or eat in the designated prison as this would defile his caste. A tent was erected for him. He restricted his diet largely to sweets and bathed in the nearby Hooghly, a tributary which carries the water of the holy Ganges to the Bay of Bengal.

Impey began the trial on 8 June, at the peak of a boiling summer. Judges rose four times a day to change their robes. The trial ended at midnight of 15 June 1775. Maharaja Nandakumar was found guilty by an all-English jury led by John Robinson, an employee of the East India Company. Impey sentenced him to death. According to Busteed, the prosecuting counsel was so “unequal to the labour of the prosecution, especially that of cross-examination” that the judges, with the exception of one, Justice Robert Chambers, “took this duty on themselves, and carried it out in prodigious detail, recalling witnesses over and over again”. [Echoes from Old Calcutta, pages 118, 119]

The charge had been fabricated; the trial rigged; the conviction was based on a statute not applicable in Calcutta, according to a ruling by Justice Chambers, a former Vinerian Professor at Oxford, in a later case. Deputations for reversal or mercy were summarily rejected.

Calcutta’s sheriff Alexander Mackrabie, Francis’s brother-in-law, found the maharaja completely composed and resigned to “God’s will” on the eve of his execution. It was Mackrabie who succumbed to emotion: “I found myself so much second to him in firmness, that I could stay no longer.” The next morning,

There was no lingering about him, no affected delay. He came cheerfully into the room, made the usual salaam, but would not sit till I took a chair near him. Seeing somebody look at a watch, he got up and said he was ready, and immediately turning to three Brahmins who were to attend and take care of his body, he embraced them all closely, but without the least mark of melancholy or depression on his part, while they were in agonies of grief and despair. [Busteed, page 135]

On 5 August 1775, a Saturday, the wail of Indians could be heard across Calcutta as the “Brahmin of Brahmins” was hanged at eight in the morning at Cooly Bazar near Fort William.

Hastings did not waste time delivering his thank you notes. Impey’s frontman Archibald Fraser, who kept the seal of the Supreme Court, was given a contract of Rs 420,000 for bridge repairs as against the previous contract of Rs 25,000 per year. Calcuttans, lost for all else except words, nicknamed Impey “Justice Pulbandi” (roughly: Justice Bridge-dealer). The irrepressible Hicky used the derisive term gleefully in a poem about a public petition against the chief justice which was sent to London:

Poolbundy once in a high fit of crowing

Exclaimed thus to Archibald Sealer the Knowing!

I told you that those dar’d sign the Petition,

Shou’d all be dispatched with great expedition!

Shall the Company’s factors, and even their clerks

Attempt upon us to send home their remarks?

Shall prentices dare to insult thus their better?

Besides that, they robe within my own door

In daily oppressing and squeezing the poor!

Jibe was complemented by parody:

A few days ago was held a Grand Council upon affairs of state… it was resolved that Lord Poolbundy should continue to hold that title for life and that a sunnud [Mughal deed] should forthwith be granted to him for another Jaghire in addition to the three he now enjoys in order to enable him to support his honour with beaming dignity and this proceeds from the love the Great Mogul bears him for his long, faithful and disinterested services. [Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, Mukhopadhyay, page 90]

The white “Great Mogul” was of course Warren Hastings.

THE LEGAL PROFESSION did not have a very exalted reputation. Hicky writes that he was known as:

the Gentleman Attorney, in contradistinction to the blackguard practitioners, of which description I am sorry to say there were several. In fact, with the exception of Messrs Palfrey and Nail, or, Foxcroft, Johnson, Jarrett [who was solicitor to the Company], and Smoult, I never met any attorneys in the company I kept, which always was the best. [Memoirs, Chapter XI]

In such a fetid environment, criminal lawyers were seldom short of a brief. A popular doggerel of the time went Jaal, juochuri, mithye katha/ Ei teen niye Kolikata (Forgery, swindling and lies are the three things that make up Calcutta). In 1795, the government prohibited all Company employees from “demanding or receiving any fees or dastoors on any pretence whatever”. Everyone, including the judiciary, shrugged off the diktat.

Impey’s Bengali dewan, Maharaja Sukhomoy Ray, built a huge palace in north Calcutta from coin which stuck to his magnetic palms on its way to the chief justice. Ray’s son, Raja Baidyanath Ray, became a city celebrity through the familiar combination of bribes for the rich and donations to the poor. He was a favourite of Governor-General Lord Amherst. It may, or may not, be a coincidence that Ray’s troubles began after Lord Amherst’s term ended in 1828. On 11 January 1830, the Calcutta Gazette broke a sensational story:

A true bill of forgery, we regret to observe, has been found against Rajah Buddinauth Roy. We say so, because it must always be a subject of regret, to see a person who moved in such a sphere as the rajah did and whose character hitherto has, we believe, been unblemished, placed in such a position as he now stands in. [Crime and Urbanization, page 98].

The raja was a partner in the newly founded Bank of India, which flooded the market with fake currency and forged government securities printed at a hideout in a “native” part of the town, Radhabazar. The courts, however, found him guilty merely of gullibility rather than crime.

Prankrishna Haldar was far more successful as a grand host, generous benefactor, and surreptitious crook. Haldar got reams of laudatory attention in newspapers like the Samachar Darpan for philanthropy, providing medicines to the poor or building a bridge across the river. He hosted mass meals during the annual Durga Puja festivals, as well as select parties for the well-heeled, where he raised conspicuous consumption to an impressive level by smoking tobacco rolled in 100-rupee notes. Prankrishna Haldar had money to burn. Never shy of publicity, Haldar placed this advertisement in the Calcutta Gazette of 20 September 1827:

Baboo Prankissen Haldar of Chinsurah begs to inform the Ladies and Gentlemen, and the Public in General, that he has commenced giving a Grand Nauch from this day, that it will continue till the 29th Inst. Those Ladies and Gentlemen who have received Invitation Cards, are respectfully solicited to favour him with their company on the days mentioned above; and those to whom the Invitation Tickets have not been sent (strangers to the Baboo) are also respectfully solicited to favour him with their company. Baboo Pran Kissen Haldar further begs to say, that every attention and respect will be paid to the Ladies and Gentlemen who will favour him with their Company, and that he will be happy to furnish them with tiffin, dinner, Wines, & c., during their stay here. [Crime and Urbanization, page 109]

High-priced singer-dancers like Nikki and Ushuran were hired for such celebrations. Nikki was in such demand that one enamoured Bengali zamindar employed her on a salary of Rs 1,000 a month.

SERVICE WITH A WILE

Being beaten with “furious blows” was the predestined fate of the “blackey”, as even brown or pale-skin Indians were called. Attitudes began to improve only after liberals like Henry Beveridge entered the civil service in 1857 at the age of 21; he would retire after 35 years. He and his second wife, Annette, would become well-known for their translation of Persian texts into English. They were benevolent towards their domestic staff of 39; but salaries were still low. The domestic payroll was an easily affordable Rs 250 a month since Henry’s salary was Rs 1800. Ali Jan the khansamah earned Rs 12; “Hurree”, or Bisheswar, the major domo and Ramyad the bearer, and Bogmonia the ayah got Rs 10 each. The Beveridges treated them like family. Annette could become motherly, scolding them for eating opium, and threatening to cut their pay if they persisted.

Beveridge (later, Lord) writes that Hurree would eat only if Annette Beveridge brought him food when he fell ill and trusted her: “You know that Hindus do not eat beef nor drink wine but when poor Hurree seemed likely to die we said he must take beef soup and drink and that we would give his brahmin priest money to forgive him. He does not know what he is getting but of course the other servants know and by-and-by when he is better, they will not eat with him, because he will have lost caste by eating our English food. It is better for him to eat it and die, is it not? I think he is ready to take anything I will give him. Poor fellow! He looks at me with such pitiful eyes when I go to see him” [India Called Them, page 206]. Food was, literally, a touchy issue. Boatmen on the river route from Calcutta to Benares preferred to throw away their food and break their pots if by any chance an English passenger stepped into their midst as they cooked meals on the bank.

Hastings did not waste time delivering his thank you notes. Impey’s frontman Archibald Fraser, who kept the seal of the Supreme Court, was given a contract of Rs 420,000 for bridge repairs as against the previous contract of Rs 25,000 per year. Calcuttans nicknamed Impey ‘Justice Pulbandi’ (Justice Bridge-Dealer)

In contrast, Edward Aitken, a founding member of the Bombay Natural History Society who served in the same years as Beveridge, hated his servants with a visceral passion. He described the lamp-handler as a greedy dogsbody in his autobiography Behind the Bungalow, which appeared in 1889: “The Mussaul’s name is Mukkun, which means butter, and of this commodity I believe he absorbs as much as he can honestly or dishonestly come by. How else does the surface of him acquire that glossy oleaginous appearance, as if he would take fire easily and burn well?” Mukkun was infuriating even when drying dishes (with the damask table napkin!) or sharpening knives: “Hour after hour the squeaky, squeaky, squeaky sound of the board plays upon your nerves, not the nerves of the ear, but the nerves of the mind, for there is more in it than the ear can convey”.

The dhobie (washerman) was a “jubilant” butcher of clothes: “Destruction is so much easier than construction and so much more rapid and abundant in its physical results that the devastator feels a jubilant joy in his work. The dhobie, dashing your cambric and fine linen against the stones, shattering a button, fraying a hem or rending a seam at every stroke, feels a triumphant contempt for the miserable creature whose plodding needle and thread put the garment together. This feeling is the germ from which the dhobie has grown. Day after day he has stood before that great black stone and wreaked his rage upon shirt and trouser and coat and trouser and shirt. Then he has wrung them as if he were wringing the necks of poultry, and fixed them on his drying line with thorns and spikes, and finally he has taken the battered garments to his torture chamber and ploughed them with his iron, longwise and crosswise and slantwise, and dropped glowing cinders on their tenderest places. Son has followed father through countless generations in cultivating this passion for destruction, until it has become a monstrous growth which we see and shudder at in the dhobie. He is not tolerable. Submit to him we must, since resistance is futile; but his craven spirit makes submission difficult and resignation impossible. If he had the soul of the conqueror, if he wasted you like Attila, if he flung his iron into the clothes-basket, and cried Voe victis, then a feeling of respect would soften the bitterness of the conquered; but he conceals his ravages like the white ant, and you are betrayed in your hour of need”.

Aitken’s fury extended to the dirzee, or tailor; and his language, while thinly varnished with humour, dipped effortlessly into rank racism. Hurree (Hari) was a “little human animal”, with pan supare (betel leaf and nut) “temporarily stowed away under that swelling in the left cheek, where the fierce black patch of whisker grows. The survival of a partial cheek pouch in some branches of the human race is a point that escaped Darwin” [Vernede, pages 118, 119, 120, 125, 126]. Some militant victims of the dhobi advocated aggression, suggesting that the only way to get even was to raid the dhobi’s hut and “ruthlessly confiscate any clothes in process of being washed or ironed, which do not belong to you” [Days of the Raj: Life and Leisure in British India, edited by Pramod K. Nayar, Penguin, 2009, page 97].

Since the dhobi or the dirzee never published a memoir, we do not know their version. But consider a telling fact: Indians who got their refined cotton washed and ironed by the same dhobi rarely had complaints. The dhobi turned into Attila the Hun only with his Western clients.

By the time the long twilight of the Raj set in, the khansamah had learnt to write accounts on paper. The artistry lay in the smaller sums, which seemed too trivial to dispute. Hence: ‘Butons for master’s trousers, 9 pies’; ‘Tramwei for going to market, 1 anna 6 pies’; ‘Making white of master’s hat, 5 pies’. If you challenged any marked cost, you got a very patient explanation of how he had bargained to cut the price. Sometimes he took upon himself the duties of a conscience. One Sahib, shopping while his wife was away, was on the point of buying a luxury when he heard a gentle murmur from his guardian servant: ‘Missis never allowing, sir’.

Sahibs might rail at the peon, the “mother-in-law of liars”, or the watchman who took a “gift” to open the gate to an outsider, but as Aitken said about Mukkun Lal, “submit to him we must”. Who else but the cook who made a bit on hens’ eggs had the expertise to select the right fish from the monjee, rowe, cutlah, quoye, sowle, mhagoor, tangra, chunah and hilsa (sable-fish) displayed on the wet stalls of a Calcutta market?

Indians had unusual ways of expressing their fluctuating feelings. One Memsahib discovered that her cook had, despite strict instructions, brought his young son to the kitchen, dressed in a new pink shirt, his hands tinkling with silver bangles. He was sitting on the slab of beef purchased for dinner. She would have upbraided the cook, but the child looked so cherubic that she said nothing. The happy cook surpassed himself that evening. However, no beef was served [Nayar, pages 98, 99, 100, 111].

When one English hostess in the south found that the clear soup was rather muddy, she decided to rise from the table and investigate. The cook had used his mundu, or thin linen wraparound, as a strainer. He was dismissed the next morning. It was slightly better, perhaps, than straining coffee through the master’s socks, as reported by the anonymous author of a superb mid-19th century guidebook for women on their way to India.

Nandakumar was neither naïve nor politically innocent; he was party to an attempted coup against Hastings. Nor was his ally Francis a saint, having filled his own pockets whenever he got the opportunity. What they did not expect was Hastings’s counteroffensive through Impeyh

The author employed a modest 17 servants, at a total salary of Rs 105 a month. The cook was her favourite; he had the skills to “put to shame the performances of an English one” in soups, cutlets, jellies, and confectionaries. He was rewarded with a handsome Rs 15 per month. She found the “butler” the most expensive and most useless. The chokera was either the master’s “dressing boy” earning between six to nine rupees, or an unpaid intern who broke “sufficient glass and china” to make his learning process an expensive one. The common view was that a “native never speaks the truth except by accident” but the Lady Resident believed this to be an exaggeration [The Englishwoman in India: For ladies proceeding to, or living in, the East Indies; Information on Outfit, Furniture, Housekeeping, Rearing of Children, Duties, Servants, Stable Keeping and Travel, by A Lady Resident, Pantianos Classics, E-book edition, first published in 1864; Chapter 5].

The following anecdote, from Chapter 6, was apparently not an exaggeration:

“Boy, how are master’s socks so dirty?”

“I take, make e’strain coffee.”

“What, you dirty wretch, for coffee?”

“Yes, missis; but never take master’s clean e’sock. Master done use, then I take.”

BABOO MOSHAI AND THE INGABANGA

The British response to a Bengali identity with foreign characteristics was ambiguous. The Raj wanted British Indians in its edifice without granting them British rights. Lodged in the limbo between white rule and brown subjugation, the Bengali Baboo found a niche in either the upper tier of inherited riches or across the high and middling professions: lawyers, doctors, magistrates, teachers, clerks. The prototype of the government employee was soon recognizable. Sedentary by inclination, garrulous by preference, supremely self-assured about his skewered grammar and hybrid diction, the Baboo confidently fished for favour through his skill at “shaheb-dhara”, or netting the Sahib.

The Sahib kept a measured distance from his creation, his derision quite vehement in private. “The type managed to stir every prejudice and preconception in the minds of the [British] arrivals, who were soon writing home to describe babus as ‘soapy’, ‘fat’, ‘oily’, ‘smooth-talking’, ‘devious’, ‘dishonest’, ‘servile’, ‘cowardly’ and ‘cringing villains’; if they were also Bengali, that only made things worse. It is not easy to understand how young British men reacted so strongly to these perceived defects of character when they would surely have been aware of worse failings among their often drunken, violent and foul-mouthed fellow countrymen,” writes David Gilmour [The British in India, page 404]. Gilmour tries to explain this thesaurus of negative epithets as the subconscious contempt felt by the victor for a race which had repeatedly succumbed to small armies under British officers despite a phenomenal advantage in battlefield numbers.

Even an ICS officer sympathetic to India like Henry Beveridge would write that the “besetting sin of Bengalees” was that they would “think and talk and talk and think for ever but… will not act”. Beveridge’s ICS colleague Sir A.C. Lyall was less polite in The Old Pindaree, quoted by Hobson-Jobson in the entry for Baboo: “But I’d sooner be robbed by a tall man who showed me a yard of steel,/Than be fleeced by a sneaking Baboo, with a peon and badge at his heel”. The dictionary adds: “In Bengal and elsewhere, among Anglo-Indians, it is often used with a slight savour of disparagement, as characterizing a superficially cultivated, but too often effeminate, Bengali. And from the extensive employment of the class, to which the term was employed as a title, in the capacity of clerks in English offices, the word has come to signify ‘a native clerk who writes English’”.

It did not seem to occur to the imperial mind that the Bengali Babu’s attitude might also lie in an awkward combination of ambition, dipping self-esteem and frustration. Hobson- Jobson quotes Sir H.M. Elliot, as writing, in 1850, that the Babus would “rave about patriotism, and the degradation of their present position”.

In any case, the Babu would not have survived if he had been inept. Rudyard Kipling saw virtue in the clerk, or kerani, of Calcutta, the “City of Dreadful Night”: “The Babus make beautiful accountants, and if we could only see it, a merciful Providence has made the Babu for figures and detail. Without him on the Bengal side, the dividends of any company would be eaten up by the expenses of English or country-bred clerks. The Babu is a great man, and, to respect him, you must see five score or so of him in a room of hundred yards long bending over ledgers, ledgers, and yet more ledgers—silent as the Sphinx and busy as a bee” [Problem Child of Renascent Bengal: The Babu of Colonial Calcutta, Narasingha P. Sil, K.P. Bagchi & Company, 2017, page 5]. These mechanics of the government’s financial mill took pride in being part of a group known as the bhadralok, with the suffix “Moshay” (a variation of Mahashoy, or respected), attached as an accolade.

Such Babus had social status, but were forced to subsist on the salaries of clerks, which led to the saying “moner babu, taka-ey kabu,” or “Babu in his mind, but short of cash”. It was the Babu, however, who displayed the sharpest instincts in the fluid game of upward mobility, sending daughters to the Calcutta Female School, founded in 1849 by John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune, with financial assistance from Raja Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee, an alumnus of Hare School and activist of the Young Bengal movement.

The first premises of the school, with 21 girls, were in Mukherjee’s home, before moving to the west of Cornwallis Square. The government took it over in 1856 and renamed it Bethune. Two students, Kadambini Ganguly and Chandramukhi Basu, became the first female graduates in the British empire. The other haven of the Babu, Hindu College, became Presidency College in 1855. Presidency became co-educational only in 1944, although Calcutta University had started graduate courses for women in 1878.

The wealthy Babu, or the dhanilok, enriched through trade, banking and brokerage, was lampooned because he had prospered under British patronage and lost his way in self-indulgence. Narasingha Sil quotes a description of dissipated behaviour: “They could be identified by deep crow’s feet under the eyes, a sign of their nocturnal orgies, shoulder long haircut [babri], black powder [misi] on their teeth, diaphanous dhoti…with black borders, chemise or shirt…made of cambric or the finest muslin, delicately creased…scarf around the neck [udani] and buckled Chinese leather shoes. These characters sleep by day, enjoy kite flying [in the afternoon] and songbird [bulbul] fights” [Problem Child of Renascent Bengal: The Babu of Colonial Calcutta, Narasingha P. Sil, K.P. Bagchi & Company, 2017, pages 10, 11, 12].

Babus had social status, but were forced to subsist on the salaries of clerks, which led to the saying ‘moner babu, taka-ey kabu,’ or ‘Babu in his mind, but short of cash’. It was the Babu, however, who displayed the sharpest instincts in the fluid game of upward mobility, sending daughters to the Calcutta Female School, founded in 1849 by John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune

The Babu was disdained by the British for finding a voice, and ridiculed by nationalists for finding a dubious one. Pearychand Mittra lambasted the dandy Babu in his novel Alaler Gharey Dulal (The Rich Man’s Spoilt Child), which appeared in 1858. An advertisement for Lipton tea, reproduced in Freedom and Beefsteaks, shows three men in the Babu’s drawing room seated at a table, wearing English coats over the Bengali dhoti; while a bearer in turban and local clothes stands in the corner with a large teapot. The wallpaper and furniture are Western. Rosinka Chaudhuri quotes a Bengali journalist, Girishchandra Ghosh, who lamented in 1862 that previous British generations had looked on Indians as heirs of a ruined noble, but Indians had now become slaves, with a bleak past and a blinkered future.

THE PUNCH AND CURZON SHOW

The English language could have been an effective bridge between the British and an influential middle class, but the two never conversed. Sahibs interacted with servants at home and subordinates at work. They spoke out of need or necessity, not out of choice. Servants had a smattering of half-pronounced English words; their Memsahibs obliged with similar hotchpotch in native lingo. A thin sliver of aspirational Indians started to use English for supplication, couched in the insincere praise of one seeking favours.

Indian English began as an imagined language.

The correspondent of the Hindoo Patriot wrote in 1857 about the classic Sanskrit play written by Kalidas, Shakuntala: “Foreigners contemplate with ecstasy the genius of our poets. The universities of Europe are not tired of pouring over the musty tomes of ancient Sanskrit literature. The Sacoontollah of Kallidas has undergone the most finished translations in Germany and in England. But amongst the people for whose forefathers the immortal bard taxed his genius, his admirable work is a sealed book almost”. Syntax sank into bathos when Indians sought the soaring heights of romantic poetry: Soft summer hours/ Freshening April showers/ Joyance rains upon me/ Weaving the chaplets you have yet to gain [Linguistic Colonialism and the Expanding English Empire: The Politics of Indians’ English, N. Krishnaswamy and Archana S. Burde, Oxford University Press, 1998, pages 95, 98].

Lord Curzon preserved a letter from an unnamed heir to a “Native State”, who was trying to explain why he had been unable to call upon the Viceroy: “I wrote to Mr A—to procure me interview with your Sublime Lordship. Although he is very aptitude, theological, polite, susceptible, and temporising, yet he did not fulfil the desire of the Royal blood. When your susceptible Lordship was at the Judge’s Bungalow, I wrote again. What I heard of your superfine Lordship’s conduct, the same I have seen from the balcony of my liberal Highness father. Your inimitable Lordship returned the complements of thousands of people that were standing on the street, but my fortune was such that I could not play before sumptuous Lordship upon my invaluable lute, which will be very relicious to the ear to hear…I hope that your transident lordship will keep your benevolent golden view on the forlorn royal blood to ennoble and preserve the dignity of His Highness father in sending the blessing letter of the golden hands.”

His Transident Lordship was so amused that he wrote in his notebook: “I find that in addition to the adjectives already quoted, he described me at one time or another as parental, compassionate, orpulent, predominant, surmountable, merciful, refulgent, alert, sapient, notorious, meritorious, transitory, intrepid, esteemable, prominent, discretional, magnanimous, mellifluous, temperate, abstemious, sagacious, free-willed, intellectual, inimitable, commendable, all-accomplished, delicious-hearted, superfine, ameliorative, impartial, benevolent, complaisant, efficient, progressive, spiritual, prudent, philanthropic, equitable.” Some of the epithets might even have been correct, like notorious and transitory, but not quite in the way that the correspondent intended.

THE LOST CHILDREN OF ANGLO-INDIA

Before 1900, the British described themselves as Anglo-Indians and their mixed progeny British-Indians were called Eurasians. This is the sense in which Hobson-Jobson uses Anglo-Indian in its definition of “Home”: “In Anglo-Indian and colonial speech this means England.” England was home, however, only for “pure” whites; it had no space for the “half-breed”.

The switch in terminology was designed to stress the Indian blood and create a category distinct from the “pure” whites of Britain. This was not an innocent variation in philology; it was a conscious decision to deny half-British Indians the right to claim Britain as “home”.

The Portuguese called their children from Indian mothers “Luso-Indian”, or “Mestizos”, and gave them rights of Portuguese citizenship even after they lost their colony in 1960.

Perhaps the best known Mestize was Jeanne Albert, also known as Jeanne Begum, from San Thome. Her second husband, Joseph François Dupleix, was the most successful French governor in India; they met after Dupleix captured Madras in 1746. The French, and Europeans like the Danes, who gave a home and workplace to William Carey, were far less colour conscious than the British. “There was no colour prejudice among the French… [by] 1790 there were said to be only two families in Pondicherry of pure blood, of whom the sons of one had married women of the country,” writes [Percival] Spear. [The Nabobs, page 62]

The British had fewer inhibitions when they were traders. In 1684, the Company directed its Council in Madras to “prudently induce” employees “to marry Gentoos in imitation of ye Dutch politics and raise from them a stock of Protestant Mestizes”. A mixed-race community was considered “of such consequence to posterity that we shall be content to encourage it with some expense and have been thinking for the future to appoint a pagoda to be paid to the mother of any child who shall thereafter be born of such marriage”. [The Anglo-Indians: A 500-Year History, S. Muthiah and Harry MacLure, Niyogi Books, 2013, pages 20, 21] “East Indians” wore Western dress topped off with a hat and were known as “Topas” (from topi, Hindi for hat); those who could afford it, sent their children to school in England, who then returned as employees of the Company.

Attitudes began to change after the Company acquired a state with the conquest of Bengal. Between 1786 and 1795, the British took three odious decisions which turned the children of British India into second-class citizens. The first was a “Standing Order” that banned an “East Indian” orphan, or a child who had lost the father, from going to England. The declared reason was undisguised and unapologetic racism:

[T]he settlement and education in England of such orphans involved a political inconvenience because the imperfections of the children, whether bodily or mental, would in process of time be communicated by intermarriage to the generality of people in Great Britain, and by these means debase the succeeding generations of Englishmen. [The Anglo-Indians ]

In plain language, half-British children would over time “infect” and “debase” pure British blood. A pernicious theory fostered in the septic environment of white supremacy, that those of mixed descent inherited the most dangerous characteristics of both races, was turned into the basis for government decisions. In a strange warp of mind, the British became convinced that they would be devoured by their own children. Lord Valentia, on an inspection tour between 1802 and 1806, described Eurasians as an evil threat, for they combined the aspirations of “natives” with the ability of the British:

The most rapidly accumulating evil in Bengal is the increase of half-caste children… This tribe may hereafter become too powerful for control. With numbers in their favour, with a close relationship to the natives, but without an equal proportion of pusillanimity and indolence which is natural to them, what may not in future be dreaded from them… I have no hesitation in saying that the evil ought to be stopped… [The Anglo-Indians, page 25]

British fathers began to treat their own children as evidence of guilt rather than love. The presence of Indian blood was pollution. Eurasians were smeared with epithets like “half-caste”, “half-and-half” and “eight annas” (16 annas made a full rupee), mustees, and creoles. Mixed marriages became taboo. Eurasians were gradually consigned to settlements, and the distance between them and the English became almost as great as between the 19th century Brahmin and the outcast, according to Spear. [The Nabobs, pages 61-64, 136-138]

In 1791, Lord Cornwallis suddenly barred East Indians from government employment. This was followed by the exclusion of all Indians from senior tiers of governance, on the specious grounds that while every Indian was irredeemably corrupt, British corruption could be contained by better emoluments.

Four years later came the decree that only men of “pure” European descent on both sides could serve in the marine, judiciary, police, or revenue departments, and enter the military merely as “fifers, drummers, bandsmen and farriers”. The last was a decision which the Company would immediately regret. Never short of hypocrisy, the authorities ordered East Indians, on pain of death, to enlist in the wars against Tipu Sultan of Mysore. As soon as Mysore was defeated in 1799, East Indians were again stopped from joining the Company army.

THE PURITY CRUSADERS

Queen Victoria’s civilian establishment, unlike her army, seemed more determined to upgrade Bengali morals than to improve the empire’s economy.

From the 1830s, printing presses at Calcutta locations such as Chitpore Road, Sobhabazar, Ahiritola and Goranhata, collectively dubbed the Battala press, began to churn out risqué literature. Attempts to curb unregistered printing in 1835 and pornographic material in 1852 were ineffective against popular demand. The conscientious Reverend James Long wrote to the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal on 1 July 1855 that “obscene pictures…are exposed to sale and hawked about in the public streets and villages and that there exists no law by which the publishers or vendors of these pictures can be punished”. He gathered a list of 500 Bengali titles designed to “suit the depraved taste of the country and accumulate the libidinous passions”. His fulminations contributed to a law against the sale of obscenity without doing much to hurt the trade.

In 1874 the government proscribed 15 Battala books and arrested hawkers on Strand Road for selling titles like Russick Turunginee (Luscious Girl), Nobo Roso Sagur (A Sea of New Juice), Ki Bhoyanak Bessya Suktee (How Powerful Is a Prostitute’s Strength), Adi Ros (Original Juice), Prem Natuck (Love Drama, in two editions) and Narir Solo Kala (Sixteen Arts of a Woman). A prim official recorded on file that he had the books translated into English to “determine whether their contents are calculated to pollute the mind or to excite corrupt passion of the reader. For the purpose of discovering the truth as to this matter, one has to read at least some portions of the book; this is no enviable task, though in the interests of humanity, it may be regarded as a duty…”

Victorian bureaucrats read pornography only out of a deep sense of duty.

Two decades later, in 1893, the secretary to the government of North-Western Provinces and Oudh (roughly equivalent to modern Uttar Pradesh) wrote to the chief secretary of Bengal protesting against an advertisement placed by Calcutta businessmen in Bharat Jiwan, a Hindi newspaper from Benares, on 31 July which offered Kamoddipan, or “lust-stirring oil”. The aphrodisiac was not cheap: “This oil enables the old to enjoy the pleasures of youth. If the nas (which means a sinew or nerve and is a slang term for the organ of generation) has been weakened by excessive sexual intercourse, onanism or some other cause, it is set right and restored to its original vigour by the application of this oil. To see the bracelet on your arm needs no looking glass. Use and see its effects. Price per tola Rs 5”.

The chief secretary of Bengal replied that four years earlier the Viceroy had, upon receiving a petition from the Calcutta Missionary Conference, ordered an enquiry led by Sir Steuart Bayley, Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal. It concluded that such advertisements were not punishable under sections 292 and 293 of the Indian Penal Code. The Battala press marched on [Calcutta in the Nineteenth Century: An Archival Exploration, by Bidisha Chakraborty and Sarmistha De, Niyogi Books, 2013, pages 158, 159, 160, 161, 162].

(This is an edited excerpt from MJ Akbar’s Doolally Sahib and the Black Zamindar: Racism and Revenge in the British Raj)

Courtesy : Open The Magazine