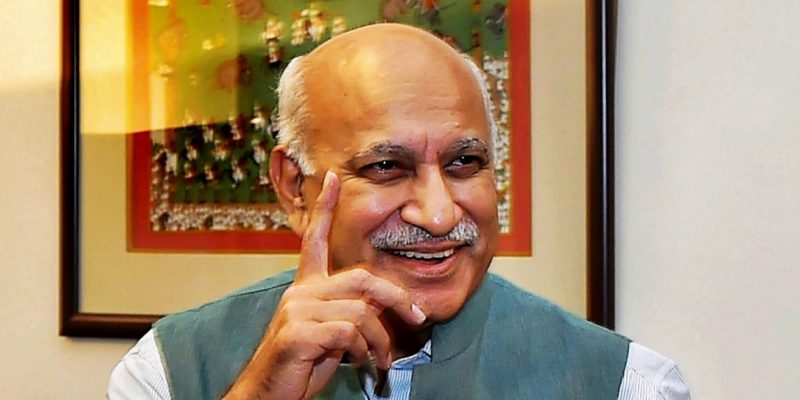

‘Why I Am Proud to be a Hindu’ : The liberating impact of Gandhi’s faith – MJ Akbar

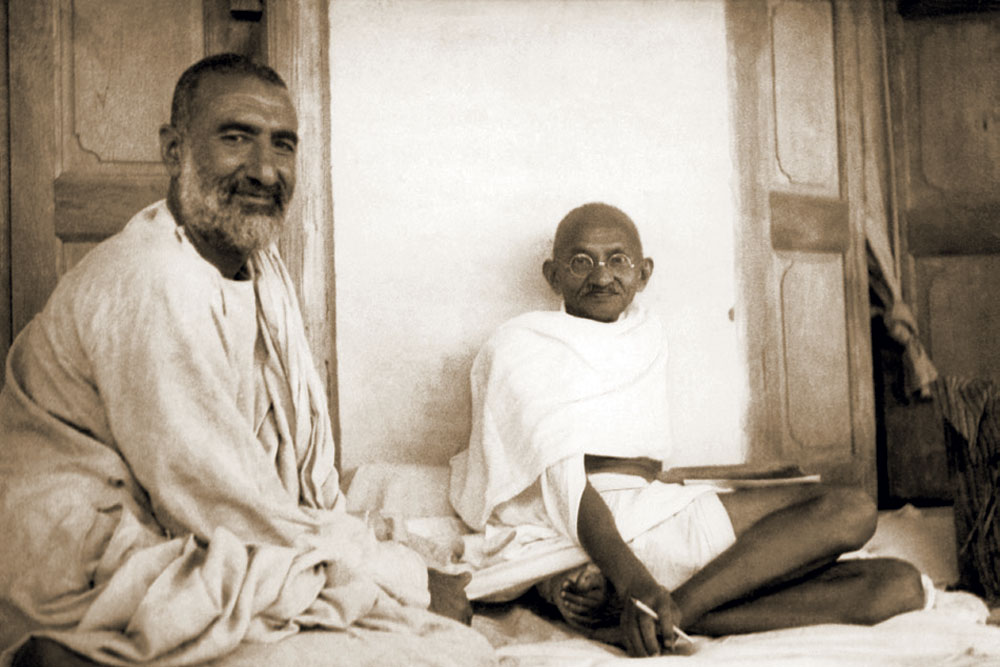

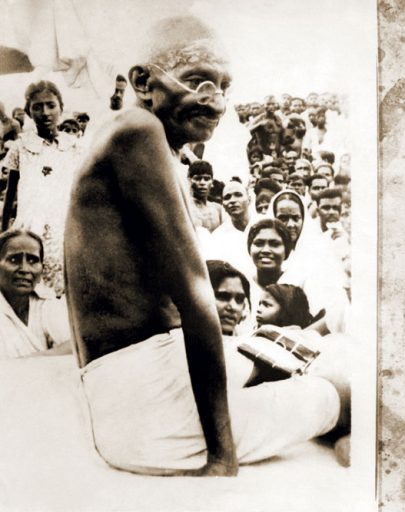

MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND Gandhi, architect of India’s liberation from British rule, wanted to spend 15 August 1947, the first day of freedom, in breakaway Pakistan rather than in India. This was neither tokenism nor a gesture of support for a country carved out of multifaith India in the name of one religion, Islam. It was a promise of defiance. Gandhi simply did not believe in the partition of India, and the creation of new, ‘unnatural’ borders by an arbitrary scalpel in a fit of what he described as momentary madness. His immediate concern was the fate of partition’s principal victims, the minorities: Hindus in Pakistan and Muslims in India. He wanted to be in Noakhali, East Pakistan, where Hindus had suffered bitterly in the 1946 riots and prevent any recurrence. Gandhi was still struggling to build hope from the incendiary debris of communal violence.

For over three decades of continuous struggle on the subcontinent, Gandhi had pursued a clear mission: the freedom and unity of India. Freedom had come, but at the cost of unity. India was split along its most vulnerable fault line, Hindu-Muslim differences. No one had fought the revanchist concept of an Islamic Pakistan with more conviction and consistency than Gandhi; no one had challenged its synthetic fallacies with more tenacity. For him, faith was harmony; how could it lead to such cruel discord? Gandhi’s pride in Hinduism lay in its philosophy of tolerance.

He could not fathom why an Indian Muslim needed to be in a different country to remain a Muslim; freedom of faith was cardinal to India’s ethos, a principle that would become a constitutional commitment in united India. Gandhi had not won freedom from the British in order to deny freedom to Indians. What new rights could a theocratic idea like Pakistan offer to Indian Muslims?

By the summer of 1947, however, Gandhi knew that between the violence of faith supremacists, the helplessness of Congress leaders he had nurtured, and some careful British manipulation, he had lost the argument. But he refused to abandon his convictions. He had been betrayed by politics, but his moral certitude never wavered. On 31 May 1947, Gandhi told an ideological brother, the Pathan leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan, known as ‘Frontier Gandhi’, that he wanted to visit the North West Frontier and live in Pakistan after independence:

By the summer of 1947, however, Gandhi knew that between the violence of faith supremacists, the helplessness of Congress leaders he had nurtured, and some careful British manipulation, he had lost the argument. But he refused to abandon his convictions. He had been betrayed by politics, but his moral certitude never wavered. On 31 May 1947, Gandhi told an ideological brother, the Pathan leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan, known as ‘Frontier Gandhi’, that he wanted to visit the North West Frontier and live in Pakistan after independence:

[F]or I don’t believe in these divisions of the country. I am not going to ask anybody’s permission. If they kill me for their defiance, I shall embrace death with a smiling face. That is, if Pakistan comes into existence, I intend to go there, tour it, live there and see what they do to me.

He also foresaw the terrible consequences of partition. On 20 July 1947, after the date of independence had been formally announced, Gandhi said in a prayer meeting in New Delhi:

I cannot rejoice on 15 August. I do not want to deceive you… India’s partition has grieved me more than it could grieve you… Unfortunately the freedom we have got today contains also the seeds of future conflict between India and Pakistan. How can we therefore light the lamps?

The ferocity of that ‘future conflict’ became visible in riots and war at the very outset. Massacres accompanied partition, and in October 1947, Pakistan started a hybrid war where the formal engagement of armies was overwhelmed by barbaric terrorism. Over more than seven decades, that ‘future conflict’ has become the longest continual war in known history.

Gandhi inherited his inclusive, embracing faith from his mother, Putlibai. She belonged to a Hindu sect known as Pranami, which practised what it preached: that all religions emerged from the same eternal being. Its scripture regarded the Muslim Quran to be as divine as the Hindu Vedas. Her syncretic values left an abiding, deep and lifelong influence on her son.

For Gandhi, Hinduism represented an embracing and ethical way of life; the depressing and often demeaning rituals that it had acquired were an accretion imposed by human beings

Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 in a hundred-year-old, three-storey house, the residence of officials who had served the small Princely States of Kathiawar in Gujarat for six generations. Their means did not permit extravagance, but neither were they indigent. As Modh Banias, they belonged to a caste within the upper echelons of Hindu hierarchy. His grandfather, Uttamchand (or Ota) Gandhi, had risen to become the diwan, or premier, of Porbandar. When he fell out with the princess regent, Rani Rupaliba, her troops attacked the Gandhi home. An Arab bodyguard protected Ota Gandhi. Gandhi’s father, Karamchand (known as Kaba), born in 1822, was appointed, in succession, the diwan of three Princely States—Porbandar, Rajkot and Wankaner. Putlibai, Kaba’s fourth wife, was less than half his age; the previous three had died, two in childbirth. Kaba viewed his work as a combination of administrative responsibility and social duty. There might have been as many as twenty guests for dinner on a regular basis, but Kaba did help out by peeling vegetables, while Putlibai took charge of the kitchen.

Gandhi admired his father’s professional integrity and his mother’s piety. ‘The outstanding impression my mother has left on my memory is that of saintliness. She was deeply religious,’ he writes in his autobiography. His father was incorruptible, with a reputation for impartiality and loyalty to the state, but not particularly orthodox. Instead, ‘…he had that kind of religious culture which frequent visits to temples and listening to religious discourses make available to many Hindus.’

His mother’s influence prevailed. Gandhi recalls that even though they were Hindu by birth, their Pranami temple priest used to read from both the Gita and the Quran, moving from one to the other, as if it did not matter which book was being read as long as God was being worshipped.

The Pranami Sampradaya, founded in the 17th century by Devchandra Maharaj (1581-1655), emerged during an era when the transformative policies of Mughal emperor Akbar were energising the expanding Mughal domain with a new amity between the predominantly Hindu population and a largely Muslim ruling elite. Devchandra came from Umarkot, coincidentally the place where Akbar was born during his father Humayun’s years of exile in the Sindh desert. At sixteen, Devchandra renounced the world in search of Brahma-gyan (knowledge of Brahma, the Supreme God). He settled down in Jamnagar, called his followers Nijanand Sampradaya, or the Self-Awakening Sect, and divine knowledge Tartam. Its doctrine of Hindu-Muslim harmony is captured by this couplet: Jo kachu kahya Ved ne, so hi kahya Kitab/ Donon bandey ek Sahib ke, par larhat paya bina bhed (That which is said in the Vedas, is also said in the Book [Quran]/ Both are children of One God, but quarrel without knowing the truth).

DEVCHANDRA’S MOST IMPORTANT disciple, Mahamati Prannathji (1618-94), travelled to Oman, Iran and Iraq, and compiled the Pranami Dharma’s scripture, Kuljam Swaroop. It incorporates passages from the Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, Quran, Bible and Torah. Honouring various religious sentiments, the sect prohibits alcohol, meat and tobacco. There are no idols in Pranami temples. With typical Indian inclusiveness, Gandhi’s mother worshipped at Hindu temples, revered Jain monks and practised their traditions like fasting. She would, recalled Gandhi, ‘…take the hardest vows and keep them without flinching…. Living on one meal a day during Chaturmas was a habit with her.’ On days when she vowed not to eat without seeing the sun, and abstain even if the sky was clouded, her worried son would stand outside, searching for a glimpse of sunshine so that he could tell his mother to break her fast. It is easy to trace the origin of Gandhi’s own deep commitment to fasting, which he developed both as a penance and a political weapon, to his mother.

When Gandhi became the leader of India’s freedom movement, his prayer meetings began with recitations from all major scriptures. He included the opening chapter of the Quran, the Surah Fatehah, in praise of the Rab al Alamin, or Lord of the Universe, alongside the litany of multifaith prayers in his ashram. The psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, who wrote a unique, if controversial, biography of the boy who became a Mahatma, comments:

His mother’s religion was of that pervasive and personalized kind which women convey to children; but it also prepared the boy for the refusal to take anybody’s word for what anything meant, either in the Hindu scriptures which he rediscovered only in his youth with the help of Western writings, or in the Christian gospels, the essence of which he tried to resurrect in Eastern and modern terms…

The natural tendency of a child, Gandhi notes, is to learn about faith by ‘picking up things here and there from my surroundings’. His nurse, Rambha, told him to ward off ghosts by reciting the name of Lord Rama, and ensure all-day protection by reciting the Rama Raksha verse each morning after his bath. Gandhi rather enjoyed the visible obligations of his caste, such as a shikha (or knot) in his hair, and yearned to wear the holy thread meant only for Brahmins. The broad family mind narrowed in one aspect. Gandhi was forbidden any contact at home with the ‘untouchable’ boy who came to clean the latrines. This injustice troubled the young Gandhi and raised questions that would later evolve into a core reformist mission within Hinduism.

Gandhi recalls that his bedridden father’s Parsi and Muslim friends would visit and discuss religion. The teenage Gandhi, nursing his ill parent, listened and learnt. A priest called Ladha Maharaj came to recite melodious dohas (couplets) and chopais (quatrains) from the Ramayana, inspiring an early love for what Gandhi would later describe as the ‘greatest book in all devotional literature’. Lord Rama became Gandhi’s ideal hero, although it was the Gita, from Hinduism’s defining war epic, Mahabharata, which became the more influential text. Gandhi described the Gita as his Dharma Grantha, or spiritual dictionary, a mirror for one’s inner self and a lodestar for one’s actions. It dealt with the ‘invisible’ war, the moral conflict, which was so much more difficult than any physical conflict. Courage was not violence; true courage was non-violence. The defining principle of Gita, action without attachment, was possible only through non-violence or Ahimsa. Non-violence did not emerge out of fear of violence. As he wrote in Hind Swaraj, if he ceased stealing because of fear of punishment, he would return to theft the moment that fear disappeared.

On 31 May 1947, Gandhi told an ideological brother, the Pathan leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan, known as ‘Frontier Gandhi’, that he wanted to visit the North West Frontier and live in Pakistan after independence

The absence of attachment led to a dissolution of the ego. Gandhi learnt Stithatprajna, the ability to remain calm when engaged in the most turbulent strife, from the Gita. The war in Mahabharata was an allegory to teach great truths, which could be applied in normal existence; for Gandhi, religion was not religion until it met the needs of the ‘hurly-burly of everyday life’. The Gita was a sacred text precisely because it was a gospel of daily existence. His own life was, as the title of his autobiography aptly puts it, a continuous experiment with truth; and truth was synonymous with religion. His Hinduism was the realisation of the permanent from the evanescent, in the spirit of Advaita philosophy. Both his private and public life were epitomised by struggle: the first to reach the highest expression of faith and the second to cleanse India of foreign rule. The strength he found in the former enabled him to pursue the latter. His personal behaviour drew from the values enunciated in the Upanishads: dama (self-control), tapas (self-discipline), mauna (silence), dana (sharing), daya (benevolence) and brahmacharya (celibacy). As Dr S Radhakrishnan explains in The Principal Upanishads, dama means reducing our wants to the minimal; overcoming anger and lust in the mind (krodham samena jayati, kamam samkalpa-varjanat/ sattva-samsevanad dhiro nidram ucchettum arhati: Brahma Purana 235, 40). ‘Austerity, chastity, solitude and silence are the ways to attain self-control,’ writes Dr Radhakrishnan. The purpose of tapas is spiritual, achieved through the elimination of natural desires and distractions of the outer world, till you arrive at the tranquillity of renunciation. Silence (or mauna) leads the soul to contemplation, curbing excesses of the tongue like flattery or backbiting. Dana is not merely generosity; it is freedom from acquisition. You cannot seek God while sitting on a throne. Daya, or karuna, is compassion; at peace with all through forgiveness. Brahmacharya (celibacy) is strength as well as beauty: sex is needed only to plant a seed for the creation of another body for the presence of a soul; excess destroys one’s body and brain.

Gandhi practised each of these principles, even at the cost of being misunderstood, particularly when, towards the end of his life, he insisted on an experiment with celibacy to the shock of friends, the horror of followers, the

bewilderment of sympathisers and the amazement of foes. He abandoned privacy completely.

He sought the ultimate tranquillity: to envy no one, to possess nothing, to fear none, to desire nothing. Detachment was something more than renunciation from the world; it was involvement for a higher purpose. The moral power sustained his credibility even when contradictions threatened to tar his reputation.

Gandhi preferred to emphasise the inclusive element in other faiths. In Islam, for instance, God is described as Rab al Aalameen, or the God of the whole universe, and not as Rab al Muslimeen, or the God of Muslims. How we worship that same eternal being is our option, which we must exercise without fear or hindrance.

He generally spoke for about fifteen minutes at his prayer meetings on whichever subject he felt merited attention. On 30 May 1947, he said in New Delhi:

I was born a Hindu. No one can undo the fact. But I am also a Muslim because I am a good Hindu. In the same way I am also a Parsi and Christian too. At the basis of all religions there is the name of only one God. All the scriptures say the same thing.

He, who found comfort and inspiration in the fact that all those who had given the world great religions were selfless, was deeply impressed by Prophet Muhammad’s asceticism when he first read about the founder of Islam in Thomas Carlyle’s Heroes and Hero Worship. The central challenge of his political life was the relationship between Hindus and Muslims; he sought harmony from the Quran, not conflict. He refused to share the view that the Quran had given Muslims some divine right to kill ‘infidels’. He could not totally deny those verses, which urged jihad or holy war, but he had a persuasive explanation: the Quran preached non-violence as a duty and violence only as a necessity. He remarked, astutely, that Muhammad had accepted suffering and humiliation in Mecca before he left for Medina to establish a state. In any case, it was not his intention to judge Islam’s or Christianity’s prophet; his belief in non-violence was independent of any scripture.

Gandhi was always ready to substantiate claim through experience and example. For instance, when questioned about war and Islam, he recalled the time he had spent during the 1946 riots, saving Muslims in Bihar and protecting Hindus at Noakhali

in Bengal.

No Bihari Muslim told me that since I was a non-believer they would kill me. Nor did the Maulvis in Noakhali say any such thing. On the contrary, they allowed the Ramadhun to the accompaniment of the dholak. All that the Koran says is that the infidel would be answerable to God. But God would demand an explanation from everyone, even from a Muslim. And He would not question you about your words but your deeds. But then those who are keen on seeing dirt can find it everywhere. There is nothing in which good and bad are not mixed up. Why, our Manusmriti talks of pouring molten lead into the ears of the ‘untouchables’! But I would say that that is not the true teaching of our [Hindu] scriptures. Tulsidas gives the essence of all Shastras in his statement that compassion is the root of all religions. No religion ever teaches us to kill anyone.

He continued his increasingly forlorn plea to prevent what, on 30 May 1947, seemed inevitable: ‘We must make it clear that even if we all have to die or the whole country is reduced to ashes, Pakistan will not be conceded under duress.’

Equality of faith was fundamental to Gandhi’s vision of a united India. Since no faith was superior, conversion was unnecessary or irrelevant. This neatly excised a major source of tension between religious communities. Conversion was forbidden in his ashram. He gave his devoted English disciple, Madeline Slade, whom he called a daughter, the name Mirabehn, but never allowed her to change her Christian religion. Her new name was Indian, he explained, not Hindu. While at school, he writes in his autobiography, ‘I sort of developed a dislike for it [Christianity]. And for a reason. In those days Christian missionaries used to stand in a corner near the high school and hold forth, pouring abuse on Hindus and their gods. I could not endure this.’

He was, as ever, consistent, whatever the time or context. In 1921, when he learnt that some Moplah Muslims in Kerala had forced Hindus to convert during communal riots, he called it ‘tyranny’ and ‘terrorism’. The anthropologist Prof Nirmal Bose recalls that on 25 November 1946, Gandhi told Bengali Muslims who had attacked a Hindu temple in Noakhali, ‘The Prophet [Muhammad] once advised Mussulmans [sic] to consider the Jewish places of worship to be as pure as their own, and offer it the same protection.’ For Gandhi, Hinduism represented an embracing and ethical way of life; the depressing and often demeaning rituals that it had acquired were an accretion imposed by human beings. But he promoted reform not with the disgust of an English lord demanding a ban on suttee, but as a deeply pious Hindu for whom such behaviour was a wretched deviation from a moral path that stretched back to the Upanishads. Social malpractice was an impurity, an alienation from the real truth of Hinduism, an assertion of base human desire against God’s universal will.

The seminal moment in Gandhi’s evolution as a radical and unique political philosopher and activist came during his two decades in South Africa.

The first Indians arrived in South Africa as indentured labour for Natal’s plantations in the 1860s. In 1893, with a change in the political structure, the rights of Indians began to be pared; in 1896, they were disenfranchised. Gandhi was twenty-three when he was hired as an attorney by a Muslim businessman, Dada Abdullah, for a modest fee of 105 pounds plus first-class return fare. He expected to stay for a year at the very most; but he remained for twenty-one years. His legal acumen was, very soon, less in demand than his exceptional courage and extraordinary leadership. He became the face and voice of the Indian struggle for legitimate rights.

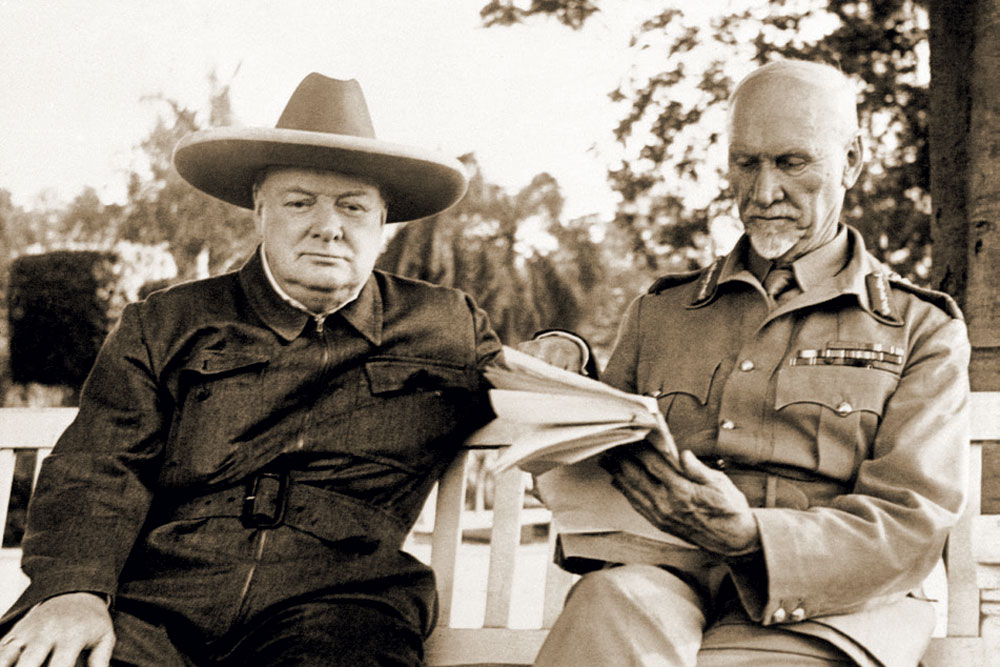

Smuts told Churchill never to underestimate Gandhi: ‘He is a man of God. You and I are mundane people. Gandhi has appealed to religious motives. You never have. That is where you have failed.’

Dutch-origin Boers had dominated the region for over two hundred years, but by the end of the 19th century, after two wars, they had lost out to the ever-expanding British Empire. Britain paid a heavy price in the Second Boer War between October 1899 and May 1902. The British had to put 400,000 men in the field under their most experienced commander, General Lord Kitchener, and suffered over 22,000 dead and more than 75,000 wounded before they prevailed. The Treaty of Vereeniging ensured self-government to Transvaal (South African Republic) and Orange Free State, but as British colonies. The Boers were co-opted into the Empire.

Indians, expecting better treatment from British rule, discovered that their situation had deteriorated. In 1906, the authorities decided to restrict Indian immigration. Among new measures was the introduction of permits with a signature or thumb impression, later embellished with a photograph, without which residence would be illegal. An Asiatic Bill was proposed. Indians condemned it (without irony) as the Black Act, and Gandhi saw nothing in the draft except hatred for Indians. On 8 September 1906, Gandhi sent a cable to Lord Minto, the viceroy of India, describing this bill as a ‘degrading, insulting’ ordinance which ‘reduces Indians to a worse status than that of pariahs’. He requested the viceroy’s intervention since the latter was ‘directly responsible for their welfare’. Calcutta, then the capital of the British Raj, was impervious. On 11 September 1906, some 3,000 anxious Indians, both Hindu and Muslim, gathered at the Empire Theatre in Johannesburg. Abdul Gani, chairman of the Transvaal British Indian Association, was in the chair. Sheth Haji Habib made an impassioned plea to pass a resolution against this law, with God as the witness. It was the first time, , that he had heard God being mentioned in such a political context; he was taken aback by Sheth Habib’s suggestion of an oath, but warmly approved of it. He stood up to explain what this meant.

We all believe in one and the same God,’ said Gandhi, ‘the differences of nomenclature in Hinduism and Islam notwithstanding. To pledge ourselves or to take an oath in the name of that God or with Him as witness is not something to be trifled with.’ He explained that ‘…there is a vast difference between this resolution and every other resolution we have passed to date.’ This was the acid test. He warned that they could face jail, hunger, hard labour, flogging and penury but could not resort to either violence or ‘internal violence’ against the oppressor. Their cause was just, their means morally pure and victory was inevitable: ‘I can boldly declare, and with certainty, that so long as there is even a handful of men true to their pledge, there can be only one end to the struggle, and that is victory’. The next day, in an accident, the theatre was destroyed by fire. The Indians took this as a welcome omen. The ordinance would meet the fate of the theatre.

That speech marked the launch of a doctrine that by 1947 would undermine the British Raj in India and, in consequence, end the age of British and European colonialism. Gandhi, after much thought, named this Satyagraha, a civil disobedience movement anchored in satya (truth), agraha (firmness) and ahimsa (non-violence), wrapped in yet another brilliant departure from conventional confrontation—empathy for the oppressor. The objective was to transform the foe into seeing the error of his ways, not to defeat him.

THE MOVEMENT WAS first described as passive resistance, but Gandhi, who had witnessed such a strategy in England, wanted a unique Indian term for a unique Indian path. This was much more than passive resistance, which Gandhi considered both weak and morally inadequate, since it had the potential of being clouded by hatred. ‘As the struggle advanced,’ he writes, ‘the phrase “passive resistance” gave rise to confusion and it appeared shameful to permit this great struggle to be known only by an English name.’ A reader of Gandhi’s journal in South Africa, Indian Opinion, suggested ‘Sada-graha’, or firmness in a good cause. Gandhi liked the word, but not enough. He altered it to ‘Satyagraha’. ‘Truth [Satya] implies love and firmness [Agraha] engenders, and therefore serves as a synonym for force,’ he wrote in Satyagraha in South Africa. This was a non-violent soul force and brute force had no place in it, in any circumstance. Satyagraha was gentle, it never wounded, it could never be violent. ‘A Satyagrahi,’ writes Dennis Dalton, ‘concentrates on the common interest and strives not for retribution but to transform a conflict situation so that warring parties can come out of a confrontation convinced that it was in their mutual interest to do so.’

Always willing to recognise truth wherever he found it, that he first witnessed the spirit of Satyagraha during the Second Boer War. Not in Boer men, who were ever ready to fight, but in the courage of the women. He writes in Satyagraha in South Africa:

[Boer women] understood that their religion required them to suffer in order to preserve their independence, and therefore patiently and cheerfully endured all hardships. Lord Kitchener left no stone unturned in order to break their spirit. He confined them in separate concentration camps, where they suffered indescribable sufferings. They starved, they suffered biting cold and scorching heat. Sometimes a soldier intoxicated with liquor or maddened by passion might even assault these unprotected women. Still the brave Boer women did not flinch. And at last, King Edward [of Britain] wrote to Lord Kitchener, saying that he could not tolerate it, and that if it was the only means of reducing the Boers to submission, he would prefer any sort of peace to continuing the war in that fashion, and asking the General to bring the war to a speedy end…. Real suffering bravely borne melts even a heart of stone. Such is the potency of suffering, or tapas. And there lies the key to Satyagraha.

Gandhi, deeply impressed by Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, truly believed that the meek would inherit the earth, and that turning the other cheek paid dividends in the rather less sacred field of practical politics.

Gandhi’s first Satyagraha lasted eight years. Its climax came in 1913, in a confrontation that caught the imagination of the world, and eventually the respect of Boer heroes, Louis Botha, then first prime minister of the Union of South Africa, and Jan Christiaan Smuts, then minister of defence and native affairs, who rose to become president of South Africa in 1939, field marshal and a friend of Britain’s legendary prime minister, Winston Churchill. A great moment of vindication came in 1913 when the viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, spoke out, not on behalf of his Empire compatriots, but in favour of Gandhi. Gandhi surely remembered how, at the start of his Satyagraha in 1906, he had been rebuffed by a previous viceroy, Lord Minto. The circumstances that drove the Satyagraha towards its decisive phase were most unusual.

In 1908, a resident of Port Elizabeth, Hassan Esop, visited India and married Bai Mariam. She did not accompany him when he returned in 1909. She came to join him in 1912, but the immigration officer refused admission. On 14 March 1913, Justice Malcolm Searle of the Cape Supreme Court passed an order confirming her expulsion on the grounds that the Muslim marriage law, which permitted polygamy and was legal in British India, was not valid in South Africa. There was an uproar, as Hindu law permitted polygamy as well at that time.

Gandhi took up the cause, writing in the Indian Opinion of 22 March 1913, ‘The meaning of the judgement is that every Hindu and Mohammedan wife is in South Africa illegally, and, therefore, at the mercy of the Government, whose grace alone can enable her to remain in the country.’ If the marriage was illegal, then wives were technically concubines, and children, being illegitimate, could not claim inheritance rights. The social and economic structure of Indian society was under threat. On 30 March, Gandhi told a meeting of Indians at the Hamidia Islamic Society’s Hall in Johannesburg that they must prepare for resistance in defence of ‘womanhood and its honour’.

In September, Gandhi prepared to put his ‘army of peace’ into battle once again; but this time its most potent soldier would be his own wife, Kasturbai, also known as Kasturba. He and Kasturbai Makhanji Kapadia were wed in 1882, when he was fourteen and she was more than six months older, then the conventional age for arranged marriages. Kasturba was incensed when she heard that according to this new law for Indians, she was no longer legally Gandhi’s wife. In that case, she said, they should return to India. Gandhi replied that it would be cowardly to do so. ‘Could I not, then, join the struggle and be imprisoned myself?’ Kasturba asked. Gandhi warned that the process would be hard, her health was poor, and she could not weaken once the hardships mounted. Kasturba refused to relent. Inspired, other women at Phoenix, where she lived, offered to join her.

On 15 September, a small band of four women, including Kasturba, and twelve men took the Kafir Mail from Durban, travelling third class and taking only the bare essentials. At Volksrust, they were arrested for crossing the border without a permit, deported on 22 September and rearrested when they tried to cross again. They were sentenced between one and three months’ hard labour in Maritzburg jail, where they were given appalling food and harsh laundry work.

Gandhi began his Satyagraha on 25 September with two demands: recognition of marriages and repeal of a punitive tax of three pounds for former indentured labour who wanted to work again. The arrest of the women had an immediate impact. Indian coalminers at Newcastle went on strike. Gandhi met them on 20 October and heard how miners had been beaten and driven out of their homes. There was little money, even for food, but the miners joined Gandhi like ‘pilgrims’, along with their wives and children, bringing nothing but a meagre bundle upon their heads. Rations were reduced to a pound-and-a-half of bread, and an ounce of sugar. Gandhi wrote in the Indian Opinion of 20 October 1913, with some satisfaction, that men were taking orders from women without argument.

ON 21 OCTOBER, MORE women were sentenced to hard labour after proudly admitting their ‘guilt’. On 28 October, Gandhi began a march of the impoverished from Newcastle to his Tolstoy Farm, where he thought he might be able to provide better sustenance. The march became news. Newspapers reported that his emaciated followers were calling Gandhi ‘Bapu’ or father. According to D.G. Tendulkar, The Times, London, reported, ‘…that the march of the Indian labourers, must live in memory as one of the most remarkable manifestations in the history of the spirit of passive resistance.’ If England was touched, India was stirred. India’s national poet, Rabindranath Tagore, sent a letter to Gandhi praising this ascent ‘not through the bloody path of violence but that of dignified patience and heroic self-renunciation’.

Gandhi was arrested en route, but the march continued. On 11 November, Gandhi was sentenced to either a fine of 60 pounds or nine months of rigorous imprisonment. Naturally, Gandhi opted for the second. Thousands were also in jail by now and anger in India rose to outrage, particularly at the harsh treatment of the imprisoned women. Protests were sent to the viceroy, Lord Hardinge. On 27 December, Hardinge announced that he would send a senior civil servant, Sir Benjamin Robertson, to assist Indians in South Africa. Donations to the South African Resistance Fund began to swell, including from princes.

Parallel to his politics ran a zeal to rid Hinduism of odious evils like ‘untouchability’, which he called satanic. Reform, he said, was necessary for the very survival of Hinduism

The South African government had begun to wilt. An Indian Grievances Commission was set up on 11 December, but since two of its members were known for their bias against Indians, it did not raise much hope. On its recommendation, however, Gandhi was released on 18 December, whereupon which he promptly announced another march for 1 January 1914. He thought some 5,000 would join; over 20,000 came. Botha and Smuts were also under pressure from friends in London, who had been sympathetic to the Boer cause. Hearts were changing, as Gandhi always said they would during a Satyagraha.

Gandhi was persuaded to postpone his march by a fortnight. Suddenly, barriers began to crumble. Smuts called Gandhi for talks and they met on 9 January. Letters were exchanged. On 21 January, there was a provisional agreement, which was signed the next day. The Satyagraha was over. The Indians’ Relief Bill legalised all Sharia and Hindu marriages; the three-pound tax was abolished. In June, Gandhi wrote to Smuts saying that a chapter that had commenced in September 1906 was finally closed.

When Gandhi sailed for home from Durban on 18 July 1914, Smuts remarked, ‘The Saint has left our shores, I sincerely hope for ever.’ The ‘Saint’ had other plans. He had also acquired a holy name: the people called him ‘Mahatma’ or great soul.

Smuts was more impressed by Gandhi than he cared to admit in 1914. This became known nearly three decades later. We learn from the diaries of Lord Moran, Churchill’s personal physician, that Smuts was dining with Churchill in London on 7 August 1942. The news of the day was Gandhi’s call to the British at a Congress session in Bombay to ‘Quit India’ and his message to Indians: ‘Do or die!’ Smuts told Churchill never to underestimate Gandhi: ‘He is a man of God. You and I are mundane people. Gandhi has appealed to religious motives. You never have. That is where you have failed.’ Churchill replied, ‘with a grin’, ‘I have made more bishops than anyone since St. Augustine.’ Smuts remained grave.

Arthur Herman, who quotes this exchange in Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry That Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age, writes:

What Smuts the philosopher could see, and Churchill could not, was the Mahatma’s supreme spirituality, which had made him revered across India and even in the West. It was a power that few other understood. Most in Gandhi’s own inner circle had given up trying. Instead, they had learned to obey it as a matter of principle. Others followed simply as a matter of instinct, as if in obedience to a natural leader… [Gandhi’s conception of life] rested on a vision of spiritual purity in which history and material things (including Gandhi’s own body) counted tor nothing… [Gandhi] valued liberty as God’s supreme achievement. It was man’s duty to live up to that standard. Without it, Gandhi believed, life was meaningless, including his own.

After the great 1857 uprising, the British were convinced about the potent political unity that faith could inspire in the subcontinent they had subdued. They also set about, carefully, to use it to their advantage.

They invested in a more cynical use of religion, to divide Indians along faith-identity, a perfectly logical option for an imperial power. They turned it into a weapon against an incipient and, in their view, unrealistic Indian nationalism. Their policies, aimed understandably at self-preservation, now sought to exploit the seams of faith, offering social or economic advantages through religious and sectional compartments, encouraging competition between Indians that could, at the throw of a statute, be escalated into conflict. In 1905, the Raj partitioned its most important province, Bengal, on Hindu-Muslim lines in support of this thesis. In 1909, through the Indian Councils Act, they increased the participation of Indians in the legislature, but included a provision unique to any voting system. Only Muslims were given the right to elect Muslims through separate electorates. This split the political ethos, for it was based on the assumption that Hindus could not be trusted with Muslim interests. A communal infection, like a cancerous cell, had been planted at the source of political life.

AT EXACTLY THE same time, Gandhi was promoting a more positive interpretation of religion as a force multiplier for unity, describing interfaith harmony as the modern idea. Gandhi wrote in the 26 August 1905 edition of Indian Opinion: ‘The time has now passed, when the followers of one religion can stand and say, ours is the only true religion and all others are false. The growing spirit of toleration towards all religions is a happy augury of the future.’ He praised a recent article in a London weekly, The Christian World, which argued that the ‘…world’s religions are linked one with the other, each having characteristics common to all others…. Religion, by a hundred different names and forms, has been dropping the one seed into the human heart, opening the one truth as the mind was able to receive it.’ Gandhi had a specific message for India:

To Europeans and Indians working together for the common good, this has special significance. India, with its ancient religions, has much to give, and the bond of unity between us can best be fostered by wholehearted sympathy and appreciation of each other’s form of religion. A greater toleration of this important question would mean a wider charity in our everyday relations, and the existing misunderstandings would be swept away. Is it not also a fact that between Mahomedan [sic] and Hindu there is a great need for this toleration? Sometimes one is inclined to think it is even greater than between East and West. Let not strife and tumult destroy the harmony between Indians themselves. A house divided against itself must fall, so let me urge the necessity of perfect unity and brotherliness between all sections of the Indian community.

When Gandhi returned home on 9 January 1915, he arrived with his principles tested in action, forged through arduous experience in conditions that could scarcely be more hostile. India’s complexities did not shift the bookends of his philosophy, Satyagraha and Ahimsa.

The first of his three mass uprisings against British rule, called the non-cooperation or Khilafat movement, took place between 1920 and 1922. It was constructed on an alliance with Muslims who were emotionally distraught at the defeat of the last Muslim world power, the Turkish Caliphate, and consumed by the thought that with Jerusalem already in British hands, the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina would also be lost to the ‘infidel’. Gandhi sympathised because he considered a brother’s grief to be his own grief. More important, however, was the fact that Muslim rage was concentrated on the British.

Gandhi had one non-negotiable condition: non-violence. Muslim leaders agreed to follow his lead, although for many of them, this was a tactical compromise. Even in the heat of an amazing mass mobilisation, Gandhi was quite ready to chastise the most important of Muslim leaders who breached his non-violence marker, and ensure that both rhetoric and action remained on a non-violent trajectory. When a firebrand stalwart, Maulana Shaukat Ali, sought revenge against the British, on the basis of an ‘eye for an eye’, Gandhi pointed out that this would leave the whole world blind.

Gandhi’s oath for Khilafat volunteers is an excellent example of what Judith Brown has described as ‘religion in action’. It reads:

With God as witness we Hindus and Mahomedans [sic] declare that we shall behave towards one another as children of the same parents, that we shall have no differences, that the sorrows of each shall be the sorrows of the other and that each shall help the other in removing them. We shall respect each other’s religion and religious feelings and shall not stand in the way of our respective religious practices. We shall always refrain from violence to each other in the name of religion.

The British had enough personal and institutional experience of war. It has been noted that they were at war in some part of the world or the other through the whole of Queen Victoria’s reign. More recently, a generation of youth had perished in the awesome bloodshed of the First World War. What bewildered them was non-violence, and its counterpart, non-cooperation.

Gandhi had honed his ideas about non-cooperation from the Gita. There were good men like Karna, Bhishma and Drona on the side of the Kauravas, he said, which suggested that evil could not survive or flourish without the support of some who were good. The British Raj, similarly, could not continue without the help of some good Indians. The purpose of non-cooperation was to remove such good Indians, both Hindus and Muslims, from the apparatus of British rule. If Hindus and Muslims united, they would become free; if they were divided, they would be slaves of the British.

Gandhi remained consistent through the long and turbulent roller-coaster ride of high-voltage events. For more than fifty years, he sang, literally, from the same hymn sheet. Religion, said his hymn, was a catechism of love, tolerance and unity. Whether in South Africa or India, for over half of a century till the end of his public career in 1948, he explained why he was proud to be a Hindu.

On 21 November 1947, Gandhi began his prayer meeting speech in Delhi by extolling the virtues of cows’ milk. He recalled the time in 1927 when, during an intense tour of southern India, he saw the ‘best cow in the whole of Asia’, at a military dairy run by a certain Col William Smith in Bangalore. He then answered three questions from the audience, ‘What is meant by “Hindu”? What is the origin of that word? Is there anything called Hinduism?’

The term ‘Hindu’, he said, did not occur in the Vedas. ‘The Greeks, under Alexander, coined it for people across the river Sindhu (Indus), changing the S into an H.

The religion of the people living in this region [east of Indus] came to be known as Hinduism which, as you are well aware, is the most tolerant of religions. It gave shelter to the Christians who had escaped from the harassment of the people of other religions. Besides, it also gave shelter to the Jews known as Beni-Israel and also to the Parsis. I feel proud to belong to the Hinduism which embraces all religions and is very tolerant. The Aryan scholars followed the Vedic religion and India was first known as Aryavarta. I do not wish that once again the country should be known as Aryavarta. The Hinduism of my conception is complete in itself. Of course, it includes the Vedas, but it also includes many other things. I do not think it is improper to say that I can proclaim the same faith in the greatness of Islam, Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Judaism without in any way impairing the greatness of Hinduism. Such Hinduism would live so long as the sun shines in the sky.

This did not mean that Gandhi accepted that Hinduism as then practised always reflected its essence. As a teenager, he had almost veered towards atheism after reading Manusmriti. Parallel to his politics ran a zeal to rid Hinduism of odious evils like ‘untouchability’, which he called satanic. Reform, he said, was necessary for the very survival of Hinduism. He became angry when water from a village well was denied to ‘low castes’, noting, acerbically, that a cow could drink this water but not a ‘Sudra’.

What he did learn from religion, in his own words, was:

[T]he conviction that morality is the basis of things, and that truth is the substance of all morality. Truth became my sole objective…. A Gujarati didactic stanza likewise gripped my mind and heart. Its precept—return good for evil—became my guiding principle. It became such a passion with me that I began numerous experiments in it. Here are those (for me) wonderful lines: For a bowl of water give a goodly meal; For a kindly greeting bow thou down with zeal; For a simple penny pay thou back with gold; If thy life be rescued, life do not withhold. Thus the words and actions of the wise regard; Every little service tenfold they reward. But the truly noble know all men as one, And return with gladness good for evil done.

If Hinduism shaped Gandhi, then Gandhi also reformed Hinduism. The story of India’s liberation from colonialism has subsumed the narrative of Gandhi’s liberating impact on the internal fault lines of his faith.

His metaphor for a post-British utopia was ‘Ramarajya’. Through the freedom struggle, Gandhi promised Indians the peace and shared prosperity of Ramarajya. He used the term because peasants and farmers would quickly understand it as a definition of change, of a new order after freedom. God could only appear to the poor, said Gandhi, in the form of work; neither strife nor poverty had any place in Ramarajya. The blood and chaos that accompanied India’s independence were the very antithesis of Ramarajya. On 19 October 1947, Gandhi lamented in Delhi:

I admit that we have won it [freedom] on August 15. But 1 do not regard it as true Swaraj. It is not the Swaraj of my conception. Nor can this Swaraj be called Ramarajya. Today we have come to regard each other as enemies. Muslims are enemies of the Hindus and the Hindus and the Sikhs are enemies of the Muslims. But Swaraj of my conception means that we do not want to regard anyone as our enemy, nor do we want to be enemies of anyone. That Swaraj has not yet come. Should the Hindus and the Muslims in India consider themselves enemies of each other? Will our brothers live in mutual animosity? … The temple and the mosque are one and the same. Then why is it that the Muslims should destroy the temples and Hindus destroy the mosques? They are equally at fault in the eyes of God…. I have already said that I shall either do or die in Delhi.

Those were fateful words.

‘Jinnah Was a Psychopathic Case’

ON Saturday, 5 April 1947, Jinnah arrived for his first meeting ‘in a most frigid, haughty and disdainful frame of mind’. It started with a famous contretemps over the publicity picture. In a number of photographs Jinnah was standing in-between Lord and Lady Mountbatten, and was seen much quoted in the next day’s papers describing himself as ‘a thorn between two roses’. That was less wit and more confusion. Mountbatten recalls: ‘Later I challenged him on this, and told him I thought he had said “A rose between two thorns”. He said, “Yes, but in my mind I was expecting Her Excellency to be between you and me”.’

WHETHER rose or thorn, Jinnah certainly took his time to become less prickly. Mountbatten recorded: After having acted for some time in a gracious tea-party hostess manner, he eventually said that he had come to tell me exactly what he was prepared to accept. I said that I did not want to hear that at this stage—the object of this first interview was that we should make each other’s acquaintance. For half an hour more he made monosyllabic replies to my attempts at conversation—but one and a half hours after the interview started he was joking, and by the end of our talk last night (6th April, when he came to dinner and stayed until half an hour past midnight) the ice was really broken.

MOUNTBATTEN said he had not yet made up his mind and was still impartial; Jinnah claimed there was only one solution, a ‘surgical operation’. Jinnah pointed out that ‘on the Muslim side there was only one man to deal with, namely himself. If he took a decision it would be enforced—or, if the Muslim League refused to ratify it, he would resign and that would be the end of the Muslim League’, a fascinating admission of his complete dictatorship, and certainty that without him the Muslim League was nothing. The assessment was not wrong. But Gandhi, continued Jinnah, had lost his authority in Congress, offering examples. Jinnah emphasised ‘that not only Mr Gandhi’s word but also his signatures were valueless’. Gandhi exercised enormous authority, but the responsibility, said Jinnah, was now with Nehru and Patel.

JINNAH, in contrast, could command obedience without explanation. Mountbatten believed that Jinnah did not understand even ‘the most elementary mechanics whereby Pakistan was to be run’, as events were to confirm. But this was a meaningless objection for the League’s faith-supremacist ideologues.

BY 8 April, the discussion had moved to the division of Bengal and Punjab. When Jinnah ‘expressed himself most upset at my trying to give him a “moth eaten” Pakistan’ and warned the viceroy against a Congress ‘bluff’, Mountbatten called Jinnah’s bluff. Since Jinnah now argued that Bengalis and Punjabis had a ‘common history, common ways of life; and where the Hindus have stronger feelings as Bengalis or Punjabis than they have as members of the Congress’ then the same could be said of a ‘great subcontinent of numerous nations, which could live together in peace and harmony; who could, united, play a great role in the world; but who, divided, would not even rank as a second-class power’. Mountbatten adds, with some relish, ‘I am afraid I drove the old gentleman quite mad, because whichever way his argument went I always pursued it to a stage beyond which he did not wish it to go’.

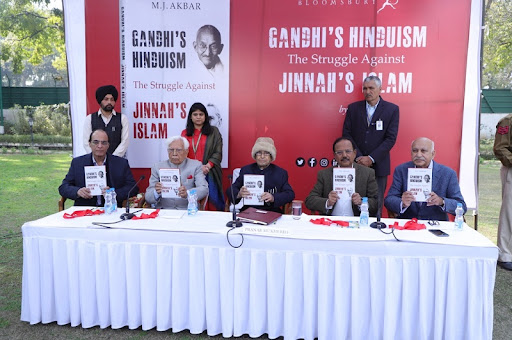

(This is an edited excerpt from Gandhi’s Hinduism: The Struggle Against Jinnah’s Islam by MJ Akbar | Bloomsbury | 450 pages | Rs 699)