A Bookworm’s Lockdown – M J Akbar

A loincloth for Prince Philip and the Quran written in Saddam’s blood

- M J AKBAR

M.J. Akbar has been editor of a range of magazines and newspapers, including Sunday and The Telegraph. He is also author of eight major books on Indian history, published to international acclaim, including India: The Siege Within, Nehru: The Making of India, Kashmir: Behind the Vale, The Shade of Swords: Jihad and the conflict between Islam and Christianity, and Blood Brothers.

Stalin flew in a lemon tree for the British at Yalta who had brought their own gin but forgot the lime (Illustrations: Saurabh Singh)

“COMPUTERS ARE USELESS. They can only give you answers,” said Picasso in 1968, the year in which Intel was founded and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey was released. Picasso didn’t change his mind. Over the last half century computers have become immensely better at providing answers, but not so good at asking questions. A good book asks questions. A better one raises questions you never knew existed. The key to a lockdown can lie in a book.

Who knew that Stalin was a fan of Tarzan and cowboy films? Or that Stalin and Roosevelt smoked the same cigarette brands: Camels, Chesterfields and Lucky Strikes? Thank you, Diana Preston, for Eight Days at Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin Shaped the Post-War World.

The Russian leader was a warm host at the conference in February 1945, where he let Roosevelt and Churchill deliberate over the last phase of the fighting, while he expanded the strategic boundaries of the Soviet Union in post-war Europe and set off the icy tremors of the Cold War. When the American and British delegations landed at Saki airport in Crimea, en route to Yalta, they were greeted with caviar, sturgeon, smoked salmon, eggs, champagne, vodka and tumblers of Crimean brandy. The British had their own gin, but someone forgot the lime; so Stalin had a lemon tree brought on a special plane.

According to Preston, and we have no good reason to disbelieve her, the term “United Nations” was chosen in the last week of December 1941 by Roosevelt and Churchill in a naked display of fraternal power. The story is best told by the author: “Late one evening in the White House they had been discussing several suggestions before agreeing to sleep on it. By the next morning Roosevelt had firmed up on the name. He wheeled himself to Churchill’s room and entered, only to find Churchill ‘stark naked and gleaming pink from his bath’. Roosevelt prepared to retreat but Churchill made his often-quoted remark, ‘The Prime Minister of Great Britain has nothing to hide from the President of the United States’. Thereupon Roosevelt said, ‘The United Nations,’ and Churchill replied simply, ‘Good!’”

The term was put on paper in the United Nations Declaration issued on January 1st, 1942 by Roosevelt and Churchill; Stalin’s Soviet Union and Chiang Kai-shek’s China signed the next day through representatives, along with 22 countries. The “United Nations” promised that no member would make a separate peace with Germany, Japan or Italy. They also agreed “to ensure life, liberty, independence and religious freedom, and to preserve the rights of man and justice”.

Eight decades later, how many countries would remain on the UN register if the principles of liberty and religious freedom were to be strictly enforced?

Footnote: The most intense German bombing during World War II was not over London during the Blitz, as we commonly assume, but over Malta (then British) in the Mediterranean. In one sustained spell, the Luftwaffe dropped 6,770 tonnes of bombs, or twice that of the Blitz, on this tiny island 17 miles long and nine miles wide.

It is well known that Churchill wanted Mahatma Gandhi anywhere but in India. The British, at various points of the freedom movement, were ready to send their bête noire to Aden, Burma or southern Africa, but did not for fear of public upheaval. But I doubt Diana Preston’s contention that Churchill suggested sending Gandhi to America during his talks with Roosevelt, adding, “He’s awfully cheap to keep, now that he’s on hunger strike”. The line sounds very Churchillian, hiding strong purpose behind trenchant wit. But the Casablanca conference took place between January 14th and 24th, while Gandhiji’s epic 21-day hunger strike in prison, which Churchill repeatedly tried to “expose” as fraudulent, did not begin till February 10th, 1943.

The first swadeshi movement was in America, not India.

I did not pick up A History of the World in 6 Glasses, by Tom Standage, in search of any lofty politics or philosophy, but during that brief spell of panic at an airport when you wonder if you have enough palliative for a transcontinental haul. The book remained unopened on the flight because the Agatha Christie I was already reading and fatigue were sufficient to induce sleep. The book remained unexplored for forgotten reasons until one began rummaging through shelves during the long Covid season of 2020-21. The glass of American rum became a mirror of democratic surge and upsurge.

In 1758, George Washington, later first president of the US, was a candidate for Virginia’s Assembly, the House of Burgesses. His campaign distributed 28 gallons of rum, 50 gallons of rum punch, 34 gallons of wine, 46 gallons of beer and two of cider to the electorate. According to my sober calculations, given that there were only 361 voters, this adds up to nearly half-a-gallon of alcohol per voter. By those standards, America’s latest President Joe Biden would have had to hand out over 40 million gallons of spiritual nourishment on his way to the White House. Democracy, however, has made progress. Instead of rum, we have opinion polls. They cost much more, but are equally heady until actual results prove them to be as illusory as intoxication.

By Washington’s standards, Biden would have had to hand out 40 million gallons of liquor

In other news: The American Revolution began not over a tax on tea, but a tax on rum.

In 1733, the British parliament passed the Molasses Act, imposing a tax of six pence a gallon upon molasses, and a tariff on sugar imported by its North American colonies from any source other than British plantations. It was the kind of protectionism that devastated Indian textiles and turned Lancashire millowners into millionaires. British sugar was inferior to the French variety, leading to lower American production and higher prices at a time when rum accounted for 80 per cent of American exports.

Rum was the people’s drink, cheaper and stronger than wine or brandy. It was drunk on every occasion, from signing a contract to buying a farm to private or public festivity. Local consumption amounted to about four gallons per year for every man, woman and child. Assuming that children did not drink, and women drank less than men, make that about six gallons for every adult male. America had high standards.

Americans responded to the Molasses Tax with a boycott of British goods. The battle cry “no taxation without representation” was first heard in the 1730s. Groups like the “Sons of Liberty” began to suggest independence at clandestine meetings in distilleries, where they fuelled their patriotism with rum punch, tobacco, cheese and biscuits. But colonisation has an inexhaustible appetite for money. London applied a further squeeze through the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Tea Act of 1773. Americans dumped British tea into the Boston harbour in 1773, and dumped Britain in 1779. But it all started with rum.

The Madman’s Library must surely be the perfect book for an insane pandemic. It is an extraordinary collection of trivia, totally useless for any professional requirement, and utterly invaluable for any conversation. The sub-title, The Strangest Books, Manuscripts and Other Literary Curiosities from History, says it all.

In the sixth century, a Chinese prince named Shuling copied the Nirvana Sutra in his own blood, taken from his fingertips, tongue and chest in a practice known as xieshu, an ascetic form of sacrifice. A bit more recently, Iraq’s dictator Saddam Hussein had the Quran written in over 50 pints of his blood, mixed with chemicals, by the master calligrapher Abbas Shakir Joudi.

A great American bibliophile, Harry Elkins Widener, commissioned the London bookbinders Alberto and Francis Sangorski to do the covers for a manuscript of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat. They took two years and used over a thousand precious jewels on leather. In 1912, an exhilarated Widener picked up his treasure and boarded a luxury liner to return home. Regrettably the name of the ship was Titanic. Neither the book nor the passenger survived.

The closer a man gets to becoming one, the more inclined he is to believe in ghosts. That is logical. Some of the finest writers of the 20th century were completely convinced about an afterworld of spirits even when quite young. William Butler Yeats’ wife, George, took 4,000 pages of “spiritual dictation” from the “other world” during the first three years of their marriage, which was published as A Vision in 1925, under the Irish poet’s name. One does not want to tempt the boundaries of humour with puns about ghost writers, but a genius generation was quite convinced about literature from the overworld.

There are 350,000 species of beetles, and only one of homo sapiens. I don’t know why. Nor does the author of The Madman’s Library Edward Brooke-Hitching, a collector of rare books. He just lets the facts sit on the page, staring at you. His beautifully illustrated work is rare too, because of content rather than antiquity. This is the classic dip-book. Open at any page, and enjoy yourself.

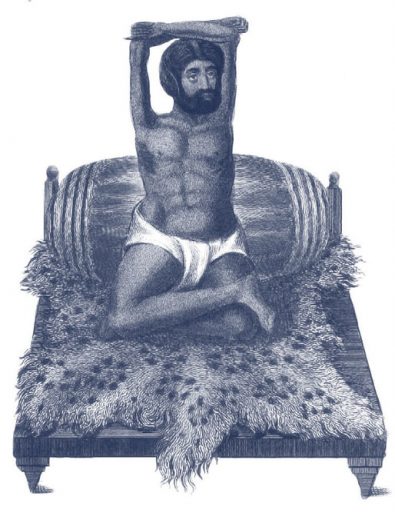

Shame on you if you sneer at the mention of sadhus lying on a bed of nails. The early 19th century text, Hindoostan, edited by Frederic Shoberi, reproduces portraits, “drawing from life”, of two mendicants who were living in Benaras in 1792. “The Fakir Praoun Poury” (Pranpuri, one presumes) is pictured sitting on a tiger skin laid on a bed, with his arms crossed over his head, a posture he adopted for four decades. Born in Kanauj, he ran away from his Rajput family at the age of nine, and began his yoga of penitence at the age of 18 during the Kumbha Mela at Allahabad. He travelled across India, and to Persia, Russia and Nepal, hands aloft.

The second fakir, the Brahmin brahmachari, was “Perkhasanund” (Prakashnand). He left home at 20.

He spent 12 years in a gufa, or cave, in Tibet, during which time his skin was nearly devoured by vermin. When he emerged from that cell he began to “lie on a bedstead, the bottom of which is stuck full of iron spikes…He never afterwards lay on any other bed. To render this penance the more meritorious, he had logs of wood burned round his bed during the intense heat of summer: and in winter he had a pot perforated with small holes hung up over him, from which water kept continually dropping on his head”. The Asian Researches published a report on this bed of nails in its fifth volume, authored by “Mr Duncan”, a former governor of Bombay.

In their portraits, both the fakirs have a slight smile. Neither is wearing anything more than a loincloth. Frederic Shoberi is amazed, but never denigrates the mendicants; he is convinced that their feats are genuine. In contrast, he is properly suspicious about jugglers who transform articles in their hands into serpents, noting, however, that “it is scarcely possible to conceive how the metamorphoses could be effected”.

He has an eyewitness account of a much more bizarre act: “A mango stone was buried in the ground before our faces, with sundry grimaces and affected incantations by the jugglers: in a short space of time, a slender tree was observed to sprout up from the spot, and in the course of an hour, it grew to the height of four or five feet, with an exuberant foliage and several green mangoes, which we were requested to pluck and taste. The process was certainly most adroitly managed, and excited proportionate pleasure and surprise,” writes the author. Since modern magicians can make the Taj Mahal disappear, creating an instant mango tree must be par for the course.

There was an age when the British wrote the best books in English. These days they write the best book reviews.

American reviewers, so prone to declamatory encephalitis, often seem to be talking to their analysts instead of readers. A British review will serve up nuggets and say a quick goodbye. The Spectator notice of Philip: The Final Portrait in its May 8th issue, mentions that Queen Elizabeth’s bridal gown in 1947 cost 1,200 pounds plus 300 clothing coupons, and she went on her honeymoon accompanied by footmen, “dressers”, 15 suitcases, one corgi and one detective. The most interesting gift that the couple received was from Mahatma Gandhi. He sent them a khadi loincloth which he had spun. Since it was clearly not long enough for a sari, it must have been meant for Prince Philip. If only the Prince had worn the loincloth…

Memorable anecdotes are the great reward of reading. This story is from an era when the world had two women as prime ministers; Indira Gandhi in India, and Golda Meir in Israel. Both were warrior-queens: they had led their nations during wars of consequence, Gandhi in 1971 and Meir in 1973. It was a pity that the two never met, because India did not have full diplomatic relations with Israel. It would have been a formidable encounter. Both were tough and towering leaders. Both could recognise a fake at twelve paces.

This is how Golda Meir once burst the ego bubble of a possibly obsequious politician: “Don’t be so humble. You’re not that great.”

Limericks are synonymous with Edward Lear, but there is nothing in the Lear oeuvre quite as delicious as these five lines written by the author of ‘The Hollow Men’, ‘Ash Wednesday’ and ‘The Waste Land’, TS Eliot, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1948 for his profound impact on modern poetry:

There was a young lady named Ransome

Who surrendered five times in a hansom.

When she said to her swain

He must do it again

He replied: “My name’s Simpson, not Samson”.

Courtesy : Open the Magazine